In the last post, we saw that the origin of Language (with a capital L) could probably be placed back a couple of hundred-thousand years (granting a huge amount of uncertainty about nearly every aspect of the problem), but there wasn't a whole lot to say about specific languages. There's an enormous expanse of time after the origin of Language that's mostly just an impenetrable murk to us. We don't even know, for instance, if humans started out speaking a single 'Proto-Human' language (a monogenesis scenario, meaning language developed just once), or whether there were multiple languages from the get-go (polygenesis). A slightly different question is whether all surviving human languages descend from a single Proto-World language (different, because it's possible that there were multiple original languages, but only one happened to leave any surviving descendent languages). These and other related questions were discussed fairly recently by Piotr Gąsiorowski in a series on his excellent Language Evolution blog, so head on over there if you want to read more about these fascinating, but largely unanswerable questions.

In this post, I'm going to leave these early periods behind and fast-forward us through the millennia -- when we slow down again, we'll still be in prehistory, but very much recent prehistory, where we're talking about thousands of years ago, not tens or hundreds of thousands.

As we pass over the intervening tens of millennia, we do see a few big things going on. Human languages spread out from Africa, reaching every continent but Antarctica. The main landmasses of the world kind of form a rough three-pointed star. Africa is one point, and Language, like humanity itself, probably developed here. It spread up into the central mass of Eurasia, and then out into the other two points of the star: in one direction up and over the Bering land bridge and down through the Americas, all the way to Tierra del Fuego; in the other down through Southeast Asia and out into Australia (though when sea levels were lower it's better to talk not about Australia, but about Sahul: the larger landmass that existed before New Guinea and Australia became separated by water).

Our planet in an Azimuthal equidistant projection (used, among other things, in the UN emblem)

Other than the fact that languages ended up across all these regions, we don't know too much about what they were like, or what their ancient relationships were. In the Americas, for instance, some have claimed that most languages belong to a single super-family called 'Amerind'. If so, we might imagine that Proto-Amerind was a single language brought over the Bering land bridge at some ancient date. But even if the Proto-Amerind hypothesis were correct, this might not be the case: maybe Amerind was just one of several early languages, and the others left few or no linguistic descendants; or maybe Proto-Amerind had already split up into sub-branches in Eurasia, which were brought over into the Americas in several distinct waves. But more importantly, the very idea of an Amerind superfamily is in serious doubt, and is not supported by any strong linguistic evidence. We know about many medium-sized language families in the Americas -- Uto-Aztecan, Mayan, Algonquian, Siouan, Tupian, Iriquoian, Salishan, Cariban, and many, many more -- but we have no idea about what earlier layers of linguistic relationships were like, and even less idea about what the linguistic landscape looked like at the time of the first peoplings of the Americas. All we can say is that, however similar or different early human languages were in distant prehistory, by the time we catch any glimpses of direct linguistic data in late prehistory they had significantly diverged the world over into thousands of distinct languages, many of which (probably around half) have no discernible relationship to any other language (these are called language isolates).

This sort of divergence is really exactly what we should expect to find. People often like to complain about the way language changes, often casting it as a matter of degeneration or corruption -- but from a linguistic point of view, it's not just a fact that languages always change from generation to generation, but one of the most fascinating aspects of language. With the inevitability of linguistic change comes linguistic divergence. If a language is spoken across an area of any size, different parts will change in different ways. Think of Latin spoken across the Roman Empire, and eventually diverging into the various Romance languages and dialects. This happened just over the last couple of millennia, and (for a fair chunk of this period) was limited to a relatively small geographic zone in Europe (and mostly Western Europe at that) -- any many of the Romance dialects remained in contact with one another, and changed along similar lines. Now imagine this sort of diversification, but multiply the timescale hundredfold, and make the geographical span global and some of the geographical boundaries very sharp (tall mountains, wide oceans, etc.), and you'll see why even if there was a single 'Proto-World', by recent prehistory the languages of this planet have gone so far down their own paths that most 'deep' linguistic relationships are thoroughly obscured.

(The case of Latin is a good excuse for me to make a very important aside: even though I'm using words like 'descent', 'relationship', and 'family, these are strictly metaphorical terms. I mean linguistic relationships only. Just because one language is descended from another, this does not mean that the speakers of that language are descendants of the speakers of the earlier language. Not all speakers of Romance languages are descended from ancient Italians, though some might be. I myself am a native speaker of English, but all of my grandparents grew up speaking one variety or another of Low or High German; as far as I know, I have no English ancestors, and even if I did, there would be no relationship between that fact and the fact that I speak English. Sometimes, but only sometimes, evidence from population genetics can be a useful piece of contextual evidence in understanding linguistic history, but as with all evidence, this sort of thing always needs to be interpreted carefully. I'll return to this topic later on in this series, but it's worth bringing it up early on, since many people, even those who should know better, are far too quick to equate languages and genes, despite the obvious reasons for caution.)

Back to the main story, we've basically already dispensed with most of deep prehistory. Languages spread across the continents, including the distant ancestor of English, which was presumably spoken somewhere in central Eurasia. When can we first pick up the scent of this language? Certainly by about five or six thousand years ago, at the stage called Proto-Indo-European, and we'll explore this layer of linguistic prehistory a lot more in this series. But what about earlier? Indo-European is just one language family in Eurasia; maybe some of these families actually go back to one ancient super-family, spoken ten thousand years ago or more (a hypothesis akin to the Amerind speculation in the Americas). This is exactly what is proposed by proponents of the 'Nostratic' macro-family (from the Latin adjective nostrat- 'of our (country)' -- you'll be shocked to learn that this name was coined by a European scholar, Holger Pedersen).

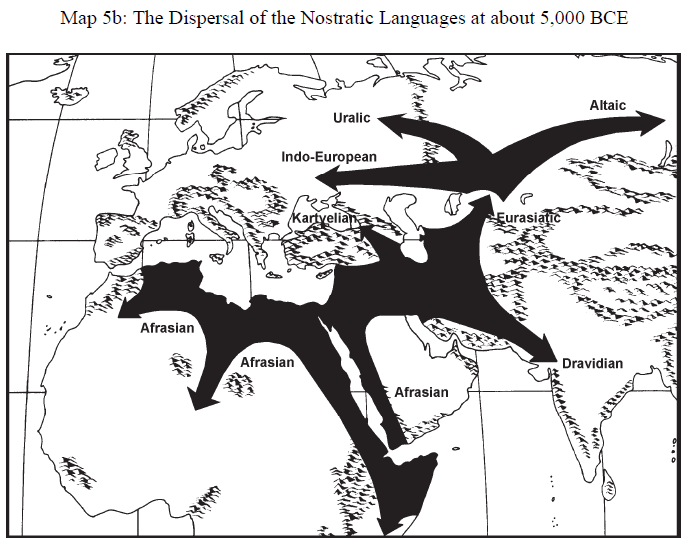

Basically, the idea behind Nostratic is that a huge number of languages spoken in Eurasia, northern Africa, and even in the northern fringes of the Americas all come from some single ancient language spoken, it is claimed, perhaps 14 000 to 17 000 years ago somewhere in Eurasia (the Fertile Crescent has been proposed as a location), and which eventually spread (in many long stages) across a large territory and many populations, diverging enormously in the process (see Bomhard 2018, pp. 304ff.). This group would include not only Indo-European (including English), but also Kartvelian (in the Caucasus), Afroasiatic (much of the Middle East and northern Africa, including Ancient Egyptian, Hebrew, and Arabic), Uralic (including Finnish and Hungarian), Dravidian (widespread in southern India), Eskimo-Aleut (across much of the circumpolar region in the northern hemisphere), Sumerian (from southern Iraq, and the first language recorded in writing), and others still.

Map of a late stage of the dispersal of some branches of Nostratic, from Bomhard 2018, p. 312.

Map of a late stage of the dispersal of some branches of Nostratic, from Bomhard 2018, p. 312.

One potential relic of Nostratic grammar is the system of personal pronouns, where there are some similarities (perhaps coincidence, perhaps trace of ancient relationship) across at least a fair number of possibly-Nostratic languages. Take English me, for instance. We're very certain that this pronoun has a long history, and we can reconstruct a Proto-Indo-European (again, we'll explore this topic soon enough) oblique pronoun stem *me- (oblique meaning that it's used for functions other than the grammatical subject). Nostraticists like to compare this with first-person pronouns in m in many other languages (though many of these are not specifically oblique forms, it's worth pointing out): Allan Bomhard cites (pp. 339ff.), among other forms, Georgian (a Kartvelian language of the Caucasus) me-, men-, mena- 'I'; Finnish (Uralic, spoken in, well, Finland) minä/minu- 'I'; Chukchi (spoken near the Bering Strait) ɣəm 'I' (the -m part is what conveys the person-number information -- compare second person ɣət 'you (singular)' -- and so might well reflect an old independent pronoun suffixed to the ɣə- bit); Etruscan (an ancient language of Italy) mi; and Sumerian me-e (among other variants) 'I'. All of this could, Nostraticists argue, reflect an ancient first-person pronoun *mi (the asterisk is important - it marks the form as a hypothetical reconstruction rather than a form actually directly attested).

How plausible is this Nostratic theory? It's hard to evaluate. It's certainly not a crackpot theory -- people propose all sorts of fanciful linguistic connections all the time, most of which haven't the slightest basis in reality, and which make no attempt at linguistic rigour. They can do this because if you compare enough languages, you'll be bound to run across some curious linguistic coincidences. Finding a few vaguely similar-looking words with vaguely similar meanings in some languages doesn't come remotely close to demonstrating, or even suggesting, a linguistic relationship. An example like putatively-Nostratic *mi- means absolutely nothing on its own, and Nostraticists quite rightly don't build their entire argument on a single correspondance like this. What really show linguistic relationships are systematic sound correspondences, and, best of all, clear traces of development from the same grammatical system (inflection morphology is particularly good evidence). We'll explore these methodological principles more over the next two posts. For now, it's worth noting that Nostraticists, unlike crackpots, take these principles seriously, and they (or at least some of them) do attempt to meet the challenge of linguistically demonstrating that Nostratic once existed. For instance, many Old World languages show a contrast between a first-person pronoun in m and a second-person pronoun in t (compare English me and archaic thee, or French moi and toi, or the Chukchi pair, mentioned above, of ɣəm and ɣət), and Nostraticists have proposed that we don't just have an isolated word-correspondence in *mi-, but a partially reconstructible pronominal system (a subsystem of grammar) with first-person *mi-, and second person *tʰi- (this is the reconstruction of Bomhard, pp. 348ff.).

But... there are problems with doing work on Nostratic. For one thing, the number of languages involved is massive. I've already made reference to Allan Bomhard's book on the subject, which runs to over 2700 pages! Treating all the linguistic data with the kind of close, detailed rigour that we ideally want is a tough call, and relatively few scholars are willing to invest the necessary time to fully engage with what might be a fruitless hypothesis. Even just double-checking and reviewing a book like Bomhard's is difficult -- I should be clear that I've only read small portions of his book, though I think I have engaged enough to have a fair sense of his general approach -- even though critical review is an essential part of working through scientific hypotheses. On the flip side, the more languages you compare, the more likely you are to find some common-looking features just by sheer chance. A number of branches hypothesized to belong to Nostratic don't have any pronoun that could be connected to *mi-; might it just be a coincidence that some do? Especially since the comparison is a little fuzzy sometimes. The Indo-European *me- is only oblique, not used for the subject. Finnish doesn't have just mi-, but longer forms in min-, with an n added on, while Chukchi has a ɣə- before the m. It's possible that these really are all reflexes of an ancient pronoun *mi-, but the the looser the correspondences and the larger the number of languages in the pool, the more likely it is that we'll find chance similarities.

There are also just plain practical problems with investigating Nostratic. Many of the potential Nostratic languages and language families are under-researched on their own rights, so that essential scholarly tools like reliable etymological dictionaries and historical grammars for particular languages and (sub-)families are often lacking or underdeveloped. There just aren't that many people working on Chukchi linguistics. And even what work has been done is sometimes fragmented across scholarly traditions. Many Eurasian languages are spoken entirely or partly within the former USSR, and there was a great deal of Soviet scholarship which is not fully integrated with 'western' research traditions. These divides have never been absolute, but they have created extra barriers and obstacles to research.

Another problem, itself related to all of these factors, is that Nostratic ultimately rests on the comparison of proto-languages which are themselves reconstructed. Since each reconstruction involves a certain amount of uncertainty (often we have to decide which of several plausible hypotheses seems most likely, not which one is absolutely certain), Nostratic involves a compounding of hypotheses, theories, and guesses: different choices in, say, how to reconstruct Proto-Dravidian or Proto-Afroasiatic could change how 'Nostratic-like' these families appear. One dramatic case is the potential 'Altaic' family: Nostraticists would see this as one branch of Nostratic, a single sub-family which in turn includes the Turkic, Mongolic, and Tungusic families (and perhaps others) -- all supposedly once spoken in the vicinity of the Altai mountains, whence the name. But many specialists now don't think that Altaic is actually a real family, and that the arguments once used to support it don't hold up under closer scrutiny. This is a clear case where changing judgements (and increasing knowledge) about one smaller group of languages could have obvious implications for the larger scale Nostratic.

In short, Nostratic is now viewed by most linguists as a highly speculative, unproven possibility. Maybe it's real, but the whole idea has too much uncertainty at too many levels to just accept. It's sort of a Schrödinger's proto-language, only the box is buried in over ten thousand years of prehistory so we can't actually open it.

So, where does that leave the history of English? We know that a long chain of languages that would become English was spoken somewhere in Eurasia in succession throughout prehistory. Maybe this language split off into other branches, some of which would develop into other Nostratic languages. Or maybe this was a more isolated language, developing without expanding and splitting for many thousands of years. However it was, eventually one particular distinct language emerged from the haze of prehistory, and by perhaps 5000 years ago (though the dating is very controversial) had developed into something we happen -- due to linguistic good fortune -- to be able to talk about with more certainty: Proto-Indo-European. This is the oldest stage of English (and of hundreds of other languages which would develop out of the same proto-language) that we can reliably reconstruct specific words for, or talk about the grammar of.

In the following posts, we'll start to explore Proto-Indo-European as the earliest reconstructible stage of (what would become) English. But as old as Proto-Indo-European is, we should remember that the past 5000 years probably constitutes a mere 2.5% or so of the time since the origin of human language. This post and the one before have already covered the overwhelming majority of the history of English.

Further Reading

Much of the literature on early language prehistory is necessarily fairly speculative, but there's been some interesting and useful work done. Johanna Nichols has published prolifically, and her 1997 article 'Modelling Ancient Population Structures and Movement in Linguistics' (Annual Review of Anthropology 26, pp. 359-384) is a good starting point, giving a global overview.

On the linguistic history of Native America, check out Lyle Campbell's excellent survey American Indian Languages: The Historical Linguistics of Native America (1997), especially chapters 3, 7, and 8. Pages 96-99 give an interesting overview of just some of the many possibilities for the early origins of Native American languages. His book is also a great starting point for further reading on any number of related topics (though of course it doesn't cover things published in the two decades since the book appeared).

For Nostratic, a one-stop-shop is Allan Bomhard's book, A Comprehensive Introduction to Nostratic Comparative Linguistics, which he has made freely available online. He's obviously convinced of Nostratic's validity and interprets the data in that light (sometimes generously so), but it's an intelligent and useful (and often wryly funny) survey of most aspects of the subject, including the history of research. There's an interesting essay collection on the subject, Nostratic: Sifting the Evidence (ed. Salmons and Joseph, 1998), which contains essays from a wide range of perspectives, and is probably the closest thing we have to a critical dialogue about the proposal.

This same book also contains Don Ringe's important article on Indo-Uralic, 'A Probabilistic Evaluation of Indo-Uralic' (pp. 153-197), which deals with the claim that, whether or not a larger Nostratic family exist, at least the Indo-European and Uralic families might go back to a Proto-Indo-Uralic (an idea supported by some tantalizingly interesting similarities in verbal endings, which are often good evidence for a linguistic relationship - but even here chance resemblance is possible). Ringe does not reject the idea of a connection between Indo-European and Uralic outright, but urges extreme caution: 'Indo-Uralic is probably the part of the Nostratic hypothesis that is MOST likely to be correct; yet sober statistical testing of the relationship can barely establish it even probabilistically' (p. 187). (Ringe's comments apply just as much to more modest macro-family proposals than Nostratic, such as the idea of a 'Eurasiatic' family.)

For more on me, and the possible significance of first-person pronouns with m contrasting with second-person pronouns with a t or t-like consonant, a good starting point is the M-T Pronouns chapter, by Johanna Nichols and David A. Peterson, on WALS (The World Atlas of Language Structures -- a fascinating and valuable resource for linguistic typology which is well worth poking around if you like languages).