In the last posts, we’ve raced through thousands upon thousands of years of linguistic prehistory, but now we’re going to slow down and start looking at the history of (what would become) English is more specific detail. We’re still in prehistory, but not deep prehistory. Perhaps some 5000 years ago, probably somewhere in central Eurasia (though both the time and place are disputed – I’ll get to these questions in later posts), we can reconstruct an unwritten language that modern scholarship has dubbed Proto-Indo-European (or PIE, for short, since that’s quite a handful to type out all the time). 'Proto' just means that it's a single language from which two or more later languages have developed – there's nothing 'original' about PIE in a fundamental sense. Viewed dispassionately, it's just one language among hundreds in ancient Eurasia, which just happened (for reasons we'll get to eventually) to get spread across a large territory, and develop from there into a pretty diverse and far-flung set of 'daughter' languages. This sort of spread and diversification is a thing languages do from time to time – we have a number of examples from better-documented periods, and probably the same sort of thing went on in deeper prehistory too.

Mmm, pie.

Mmm, pie.

Probably the most obvious question about PIE is, if it was never written down, how do we know about it? This is the question I’ll try and answer in this post and the next, before actually getting down to what PIE is all about in its own terms. Basically, all answers boil down to that fact that we find certain features in languages we do have records of, which are best explained by the hypothesis that the languages in question developed from a single older language (much like – to return to an ever-useful example – the Romance languages developed from a type of Latin). Or in plainer language, we find features that are too similar in detail to be due to chance (or to linguistic universals, or onomatopoeia, and which too thoroughgoing to be due just to influence from one language on its neighbour).

One thing we look for are regular equations in pronunciation – phonological correspondences – which is where explanations of linguistic reconstruction usually start (and all too often end). I’ll talk more about these next time, but today I’m going to focus on something maybe even more fundamental: grammar, and in particular, what linguists call inflectional morphology.

Modern English isn’t a terribly highly-inflected language. We have a little marking in the present tense of verbs (I walk versus she walk-s), and most verbs change form a bit in the past tense (walk versus walk-ed, spit versus spat), and our nouns mostly distinguish singular and plural forms. Probably the richest inflection we have today is our set of pronouns, where we can distinguish subjective forms like I, objective forms like me, and possessive forms like my (these aren’t distinctions that a language has to make – languages such as Malay can use a single form for any of those functions. These kinds of things are called ‘inflectional morphology’ by linguists. Some languages do even less of this sort of thing than English, but many do much, much more.

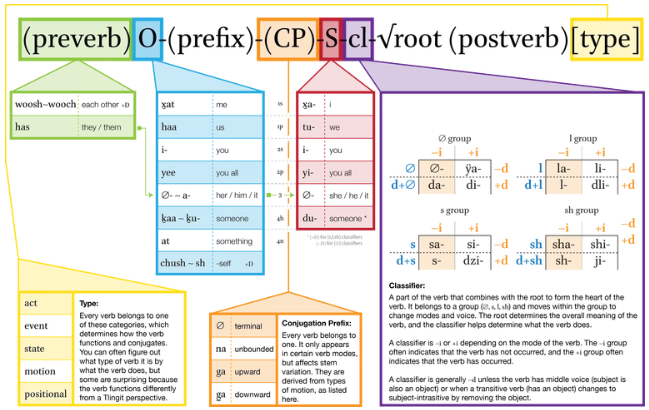

Structure of a Tlingit (American Pacific Northwest) verb, an example of rich morphology.

Structure of a Tlingit (American Pacific Northwest) verb, an example of rich morphology.

In the case of Indo-European (IE), one of the things that makes the reconstruction of a prehistoric ancestor language so secure is that many of the older IE languages are richly inflected, and we find the same quirks of morphology in language after language. There are a lot of ways this plays out, but today I’m going to focus on just one example: the word is. This is a nice basic word, and is a core part of the grammars of many Indo-European languages. If we take three of the older Indo-European languages, Latin, Ancient Greek, and Sanskrit, we can see an obvious similarity in their words for is: Latin has est, Greek a slightly longer form esti, and Sanskrit has asti. From these forms, and using a good deal of further contextual evidence about sound correspondences (which I’ll get to in due course), scholars for a long time reconstructed a PIE form *esti from which all these other forms developed. The asterisk, as a reminder, marks this form as a reconstruction, something not attested, but inferred using comparative reconstruction. (Today, we actually usually reconstruct this word as *h₁esti, with a funny-looking h₁ tacked on the front; this is a matter for later post, and I’ll ignore this and other ‘laryngeal’ consonants today, just to keep the clutter down.)

Correspondences like est, esti, asti are interesting enough already, since is is a fairly basic kind of verb, and less likely to be borrowed around a lot. But still, this could be coincidence. Things get a little more interesting when we look at the grammatical rules of each language, and find out that we can divide up these words into smaller bits. This is clearest in Sanskrit, where asti can be clearly divided into two chunks: a ‘root’ (the bit that actually carries the core meaning of the word) as-, and an inflectional ending -ti, which marks this as specifically a third-person singular form (so meaning ‘she is’, not a different person like ‘I am’, and not a different number like ‘they are’). We can do the same thing with Greek: it’s not just esti, but es-ti. Latin est is a little more reduced, but we can still understand it as es-t.

Linguists love tree metaphors. A 'root' is the most basic unit of meaning in a language, before any suffixes have been added or other morphological process have done their work.

Linguists love tree metaphors. A 'root' is the most basic unit of meaning in a language, before any suffixes have been added or other morphological process have done their work.

This is much better evidence now. It’s not just a single word that happens to look vaguely similar, but single word that is formed in the same way. This is a morphological correspondence, and shows that these three languages all agree closely in this point of verbal inflection. And it gets better still when we look at the plural counterpart of is, the word meaning ‘(they) are’, which shows a curious relationship to the singular. In Latin, this is sunt, and Sanskrit has santi (Greek has some funny sound changes here, so I’ll leave it out for now). Just like with the singular, we can divide these words into a root and an ending: Sanskrit has not santi, but s-anti, and Latin has not sunt, but s-unt. Now we’re really getting somewhere. It’s not just a couple of words that look alike, but a rather strange grammatical process shared by both Latin and Sanskrit: the singular has a longer form of the root, es- or as-, plus a relatively simple ending, -t or -ti; by contrast, the plural has a reduced form of the root, just the consonat s- in both languages, while the ending is a something rather fuller, -unt or -anti.

A similar pair of words can be found in a whole bunch of Indo-European languages, not just Latin and Sanskrit. One of the oldest IE languages we have records of is Hittite, where is is ēš-zi (pronounced something like ‘es-tsi’), and the plural is aš-anzi. Even plenty of more recent Indo-European languages have something like this: Russian, for instance, has singular jes-t’ and an archaic plural s-ut’, and the Germans use singular is-t and plural s-ind. Modern English is a bit more worn down. Our singular form is has lost all trace of the original ending *-ti, and our plural form are has an entirely different origin. But Old English, spoken a good millennium and more ago, had a plural form sind alongside singular is.

This is a rather weird alternation, and one typically found most robustly in the earliest-recorded Indo-European languages – and not really found in languages we’d put in other families. A good hypothesis to explain why we find this same odd alternation in all these languages is simply that they all descend from a single, unrecorded proto-language – PIE – and that the languages that show this alternation have just preserved a morphological feature in common. We can suggest a (simplified) reconstruction of two forms of this verb in PIE, a starting point from which we can derive all the forms actually found in texts or used today: a third-person singular *es-ti ‘is’, and a plural *s-enti ‘are’. Note the asterisks! The hyphens in these forms show the internal grammatical makeup of each form: we’re reconstructing grammar as well as sounds.

Of course, one verbal correspondence like this, even in such a basic verb as ‘to be’ and including such a specific set of grammatical correspondences, doesn’t really prove anything on its own. But with Indo-European, this is just one example among countless others. All sorts of things, from verbal stem formation (things like what kinds of tense-like distinctions are made, not to mention the specific endings and alternations used to express these distinctions) to noun endings to the use of particles to the system of pronouns – all of these show comparable sorts of correspondences and morphological peculiarities.

It’s grammatical features like these that really caught the attention of linguists in the late 18th and early 19th century when the reconstruction of Indo-European really began in earnest. There's a very famous statement by a guy named Sir William Jones, a British judge in colonial India who was struck by the affinities between the Classical Greek and Latin he'd grown up with, and Sanskrit, one of the classical languages of India, which he was learning for his new job:

The Sanscrit language, whatever be its antiquity, is of a wonderful structure; more perfect than the Greek, more copious than the Latin, and more exquisitely refined than either, yet bearing to both of them a stronger affinity, both in the roots of verbs and the forms of grammar, than could possibly have been produced by accident; so strong indeed, that no philologer could examine them all three, without believing them to have sprung from some common source, which, perhaps, no longer exists...

(The Third Annual Discourse; my emphasis.)

Even after a couple more centuries of work, morphological arguments remain among the best support for the hypothesis that all the later IE languages really developed out of a single, older Proto-Indo-European. The other great pillar of linguistic reconstruction comes from shared vocabulary linked by regular sound correspondences, which I’ll turn to in the next post.

Further Reading

I'll get to some references for Indo-European in later posts, and for now just mention a couple of good resources on historical linguistics and reconstruction in general. There are lots of general introductions to the subject, including Hans Henrich Hock's Principles of Historical Linguistics (1991) and slightly more recently Larry Trask's Historical Linguistics (Robert McColl Millar edited a revised edition of this in 2015), among many others. If you’ve got a bit of grounding already in linguistic reconstruction, and what to dig more into the theories and principles that justify this sort of work, I highly recommend Mark Hale's Historical Linguistics: Theory and Method (2007). There's also an excellent classic discussion by Henry Hoenigswald, Language Change and Linguistic Reconstruction (1960), though this is a pretty technical read.